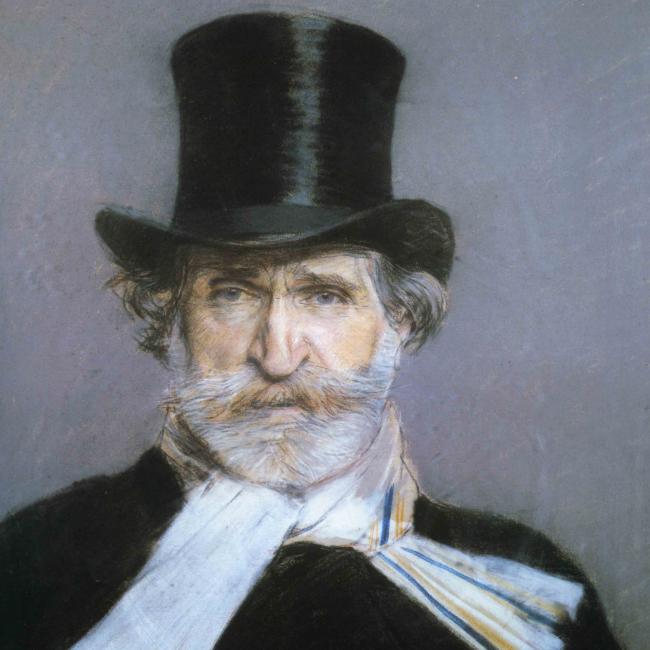

Verdi

Born: 1813

Died: 1901

Giuseppe Verdi

Giuseppe Verdi (born October 10, 1813; died January 27, 1901) was never a theoretician or academic, though he was quite able to write a perfectly poised fugue if he felt inclined. What makes him, with Puccini, the most popular of all opera composers is the ability to dream up glorious melodies with an innate understanding of the human voice, to express himself directly, to understand how the theatre works, and to score with technical brilliance, colour and originality.

Quick links

Giuseppe Verdi: a biography

The greatest of Italian opera composers was the son of a village innkeeper and began his long musical career as an organist, taking over duties at the local church when still a small child. His father sent him off to Busseto for formal music studies, thence (1821) to the home of Antonio Barezzi, a local merchant and patron of music. Barezzi supplied the funds for the young Verdi to progress to the Milan Conservatory, where his protégé failed the entrance examination due to ‘lack of piano technique and technical knowledge’ according to some sources, ‘over-age and insufficiently gifted’ according to others.

See also: Top 10 opera composers

Verdi persevered in his ambitions by taking private lessons. After his studies with one Vincenzo Lavigna, from whom he acquired a thorough mastery of counter point, fugue and canon, Verdi applied for the post of maestro di musica in Busseto. He was turned down but instead appointed director of the Philharmonic Society.

Family and early works

In 1836 he married Margherita Barezzi, the daughter of his patron, but tragedy intervened: their two infant children died and in 1840 his beloved young wife died of encephalitis. During these four years he had completed his first opera, Oberto, conte di San Bonifacio, and moved to Milan; La Scala mounted the work with some success and Verdi was given a contract to write more for the opera house. He was 27. His last opera, Falstaff, would be mounted at the same theatre in 1893, when he was 80.

See also: Top 10 Romantic composers

Un giorno di regno, a comic opera completed in the face of personal tragedy, was produced in 1840 but was a fiasco. Its failure convinced Verdi he should abandon his operatic ambitions but the impresario Merelli persuaded him to undertake a third work, this time using the biblical subject of Nabucodonosor – or Nebuchadnezzar – later shortened to Nabucco. It was a turning-point in Verdi’s career and also for Italian opera. Here, for the first time, he found his own individual voice (though still much influenced by Rossini and Donizetti); here was the successor to Bellini and Donizetti, and Verdi’s fame spread throughout Italy. His next success, again a historical subject, came with I Lombardi alla prima crociata, followed by another based on Victor Hugo’s drama Ernani. This time the subject was more overtly political, the life of a revolutionary outlaw, and the work was acclaimed.

The first masterpieces

For the next eight years from 1851, one opera followed another with varying success. During a stay in Paris, where a French production of I Lombardi was being given (renamed Jérusalem), Verdi renewed his acquaintance with the soprano Giuseppina Strepponi, who had created the role of Abigaille in the original production of Nabucco. After living together for several years, the couple were married in Savoy in 1859. By then, Verdi had written the three masterpieces that were to make him famous throughout the civilised world. The fact is that none of the subsequent operas had come close to the successes of Nabucco and Ernani. Then, using another drama by Victor Hugo, Le roi s’amuse, he composed Rigoletto. Soon every barrel organ in Europe was playing ‘La donna è mobile’, the teasing aria of the lecherous Duke. Neither this number (which Verdi kept under wraps until the dress rehearsal for fear that someone would steal what he knew to be a hit tune!) or, indeed, the whole opera show any sign of diminishing in popularity 160 years later.

Rigoletto alone would have been enough to perpetuate his name as a fine composer of operas and Verdi would have ended up as another Mascagni or Leoncavallo. But to follow that with two more masterpieces (and within the space of a couple of years) and still have some of his greatest works ahead of him guaranteed him a place among the immortals of music. Il trovatore received its first performance in Rome in January 1853; La traviata followed less than two months later in Venice. By the age of 40 he had eclipsed Meyerbeer as the most acclaimed living composer of opera.

Two years elapsed before his next work, his first opera in French, Les vêpres siciliennes, which was given a rousing reception at its premiere in Paris in 1855, despite the fact that it dealt with the slaughter in medieval times of the French army of occupation in Sicily. Another two years, another triumph: Simon Boccanegra (1857). The pattern was repeated by the first performance in 1859 of Un ballo in maschera.

Music and politics

Verdi was a fervent supporter of the Risorgimento, the reorganisation of the numerous small Italian states into one country. The theme of resurgent nationalism in his early operas, the frequent clashes with the censor (who suspected him of revolutionary tendencies), his political career in the 1860s when he sat for five years as a deputy in that part of Italy already unified – all these things endeared him to the general public. The symbol of the nationalist movement was Vittorio Emmanuel, the future King of Italy. By coincidence, the initials V-E-R-D-I stood for ‘Vittorio Emmanuel, Re D’Italia’ and everywhere, all over Italy, the composer’s name/political slogan was to be seen. The cries of ‘Viva Verdi’ could be heard as vociferously in the opera house as in the street. Verdi, however, disliked direct involvement with politics and withdrew from the first Italian parliament. (He was made a Senator in 1874, an honorary office which made no demands on him.)

During the summers, he and Giuseppina lived on a huge farm in Sant’ Agata, enjoying a simple peasant existence. The winters were spent in their palatial home in Genoa. His frequent foreign travels included a special trip to St Petersburg in 1862 to see the first performance of his latest creation, La forza del destino, which the Imperial Opera had commissioned.

The next milestone in Verdi’s grand procession was his flawed masterpiece Don Carlo (1867), a huge, sprawling affair subject to revisions and cuts (it was not given in its original version until a century after the premiere), which many opera lovers cite as the zenith of grand opera. In most people’s minds, though, it is his next creation that embodies all that grand opera should be.

Aida and Falstaff

Verdi was commissioned by the Khedive (Viceroy) of Egypt to write a piece for the new opera house in Cairo. He requested a fee of $20,000, an enormous amount in those days, and received it without a murmur. Though the score of Aida was completed by 1870, the premiere had to wait until Christmas Eve 1871. The first performance was an international event but Verdi, who hated such glitzy occasions and loathed travelling by sea even more, refused to attend the first performance. Instead, he stayed in Milan to rehearse the singers for the forthcoming Italian premiere of Aida. The Khedive’s assistant wired him from Cairo that the reaction had been one of ‘total fanaticism…we have had success beyond belief’.

The death of the Italian poet and patriot Alessandro Manzoni in 1873 prompted Verdi to write his great Messa da Requiem. Then, for the next 13 years, he retired to the country and wrote nothing. It would have been reasonable to expect no more but, using a fine adaptation by Arrigo Boito of Shakespeare’s Othello, he entered a notable Indian summer. Verdi was 79 when he completed his final opera, Falstaff, using material from The Merry Wives of Windsor and Henry IV, another collaboration with Boito. These two works constitute the high-points of Italian opera, showing that Verdi’s creative powers, far from waning, had increased. After the premiere of Falstaff, the King of Italy offered to ennoble him and make him Marchese di Busseto but Verdi declined. ‘Io son un paesano,’ he told Victor Emmanuel.

Final years

Giuseppina died from pneumonia in November 1897. Verdi was desolate and gradually lost the will to live, his sight and hearing deteriorated and he suffered paralysis but, setting aside 2,500,000 lire, he founded the Casa di Riposa per Musicisti in Milan, a home for aged musicians. It is still in operation, supported by his royalties. In 1898 he composed his last work, the Four Sacred Songs. He spent the Christmas of 1900 visiting his adopted daughter in Milan. It was here, at the Grand Hotel, that he died from a sudden stroke. He was 87. A quarter of a million people followed his funeral cortège on the way to his final resting place in the grounds of the Casa di Riposa.

The Gramophone Podcast

Verdi's music explored, with James Jolly and Richard Wigmore

Key recording

Aida

Erwin Schrott (baritone), Jonas Kaufmann (tenor), Ekaterina Semenchuk (mezzo-soprano), Marco Spotti (bass), Anja Harteros (soprano), Eleonora Buratto (soprano), Erwin Schrott (bass), Paolo Fanale (tenor), Ludovic Tézier (baritone) Orchestra dell'Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Coro dell'Accademia Nazionale Di Santa Cecilia / Antonio Pappano (Warner Classics)

'As fine an all-round Aida as the gramophone has yet given us.'

Gramophone Digital Club

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £9.20 / month

Subscribe

Gramophone Club

- Print Edition

- Digital Edition

- Digital Archive

- Reviews Database

- Events & Offers

From £11.45 / month

Subscribe

If you are a library, university or other organisation that would be interested in an institutional subscription to Gramophone please click here for further information.