Fluxus: Historical Origins and Contemporary Resonances

by Natilee Harren

What is Fluxus? Fluxus was launched in 1962 as an interdisciplinary,

neo-avant-garde artist collective, whose organized activities were spearheaded

by the Lithuanian-American artist and designer George Maciunas.

The group was primarily active in the United States, Germany, France, and Japan

through the 1970s, although some would argue that Fluxus is still alive today.

While Fluxus has acquired the reputation of being an unrepresentable or undefinable art movement, similar to how Dada and Surrealism were once perceived, that reputation may simply indicate that we haven’t yet arrived at a satisfying framework for understanding what Fluxus artists were up to. A prevailing myth has it that Fluxus was anti-art, anti-object, and promoted chaotic experimentation with no order or logic. The reality was that Fluxus artists had utopian ambitions, and their unusual tactics were part of a coherent strategy. Rather than eliminating art, they sought to dissolve its boundaries in order to infuse everyday life with heightened aesthetic awareness and appreciation. Fluxus artists looked for value in the commonplace, believing that art can be anywhere and belong to anyone. Toward this project, and particularly relevant to the LA Phil’s current celebration of this eccentric, multi-faceted phenomenon, Fluxus adopted a revised definition of music as a kind of conceptual framework for broad transformation across the arts, which I endeavor to explain here.

Fluxus was one of the most diverse avant-garde artist collectives of its moment. Participants included artists who were women, who were queer, who were African American, who were from East Asia, and yet these identities were treated with an uncommon fluidity and criticality for the time. An a-national, polyglot community, Fluxus artists were citizens of the world; they traversed a self-defined international network, and the spirit of generosity and exchange in their work countered Cold War paranoia and the retrenchment of national boundaries.

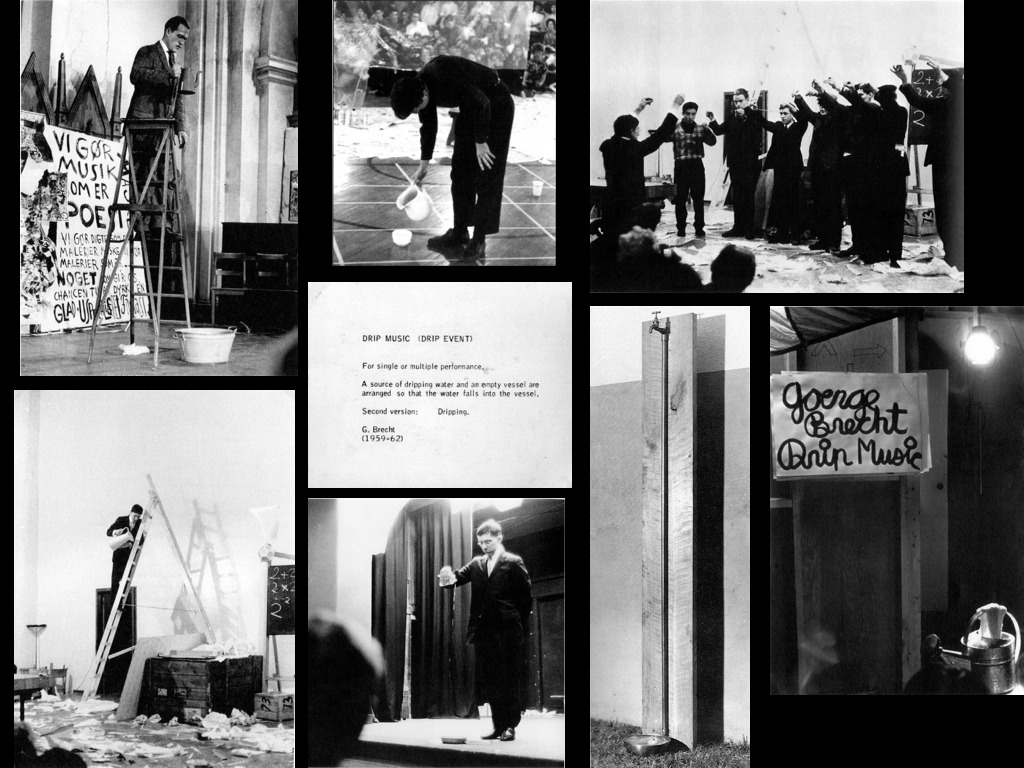

Fluxus artists’ new media works further challenged the boundaries between established modernist aesthetic categories, through strategies of indeterminate or open form, flexible and/or collective authorship, participation, and by accepting diverse interpretations of their works. A Fluxus work almost always entails multiple realizations and therefore multiple authors, performers, and audiences. If we look at the main modes of Fluxus production—an experimental performance practice complemented by the publication and distribution of scores and multiples—it becomes clear that the common denominator of Fluxus practice was a reliance on scores and other forms of realizable instruction. For example, in Fluxus performance practice, emblematic works such as George Brecht’s Drip Music (Drip Event) (1959-1962) gradually morphed in appearance from concert to concert, producing also sculptural versions. And by design, Fluxus’s editioned multiples, whose production was overseen by Maciunas, never promised to contain the same items from one “copy” to the next. In work after work, a general set of processes or qualities combine and materialize in unique, specific situations. The resulting, manifold outcomes of an individual Fluxus score or idea can be seen as inherently relatable to one another.

Scores, which imply a compositional process that is process-oriented, iterative, and often delegated, were thus a perfect vehicle for bridging varied artistic mediums and disciplines and for unifying the experiences of art and life. Fluxus artists’ utilization of scores was a major contribution to the post-modern expansion of artistic practices in the 1960s and a crucial tool in their efforts to look beyond the art world—to related fields like music, theater, literature, architecture, and design—for models of art’s production and distribution.

The first public Fluxus festival was held at the Museum Wiesbaden, Germany, in September 1962, kicking off a European concert tour that traveled to Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Paris, Düsseldorf, Stockholm, Oslo, and Nice, and lasting into the spring of 1963. Core participants included Maciunas, Benjamin Patterson, Emmett Williams, Dick Higgins, Alison Knowles, Nam June Paik, and Wolf Vostell. The events in Wiesbaden, documented in this entertaining German TV newsreel, set the terms of Fluxus’s engagement with art and music, ultimately questioning conventional understandings of both. It is telling that the first Fluxus festival took place in the concert hall of an art museum. Works performed there, such as Patterson’s Variations for Double-Bass (in which Patterson elicited sounds from his instrument using everyday objects, extending the prepared piano of experimental composer John Cage), explored the non-virtuosic sonic capacities of classical instruments and, conversely, discovered the musical dimensions of common objects, gestures, and language. Patterson’s Paper Piece, also presented during the European concert tour, revealed the surprising sonic, visual, and material range of simple paper while also being inherently participatory, as reams of papers were unfurled or thrown into the audience.

A crucial origin of Fluxus ideas was John Cage’s experimental composition course, taught at the New School for Social Research in New York in the late 1950s. In retrospect, the course can be seen as the laboratory in which Fluxus ideas were incubated. Figures including Higgins, Brecht, Al Hansen, Allan Kaprow, and Jackson Mac Low were introduced to the experimental compositions of Cage alongside those of other New York School composers, namely Earle Brown, Morton Feldman, and Christian Wolff, which played with indeterminacy and ambiguity through unconventional prose instructions and diagrammatic drawings. According to the accounts of Higgins and Brecht, Cage’s definition of music presented to students on the first day of class was simply “events in sound-space.” This basic definition encouraged participants to consider the relationships between composer, notation, performer, sound, and listener as being fundamentally non-hierarchical and deeply integrated. In essence, the composition of works for performance was understood as a practice of framing experience.

Fluxus publications and multiples, which began to appear around 1963, were also to a certain extent an artifact of Cage’s class. Using readymade, familiar, utilitarian objects was a pragmatic solution: it enabled Fluxus artists to make their editions accessible, non-intimidating, cheaply and in many copies. Beyond the New York School’s influence, the embrace of gag-like humor was uniquely Fluxus, deployed as integral to the critical project of deflating the seriousness and hierarchy of the elite art and music worlds as well as 1960s commodity culture in general. Fluxus works often deliberately disappoint or reroute our expectations of fulfillment through experiences of pristine goods or carefully choreographed experiences.

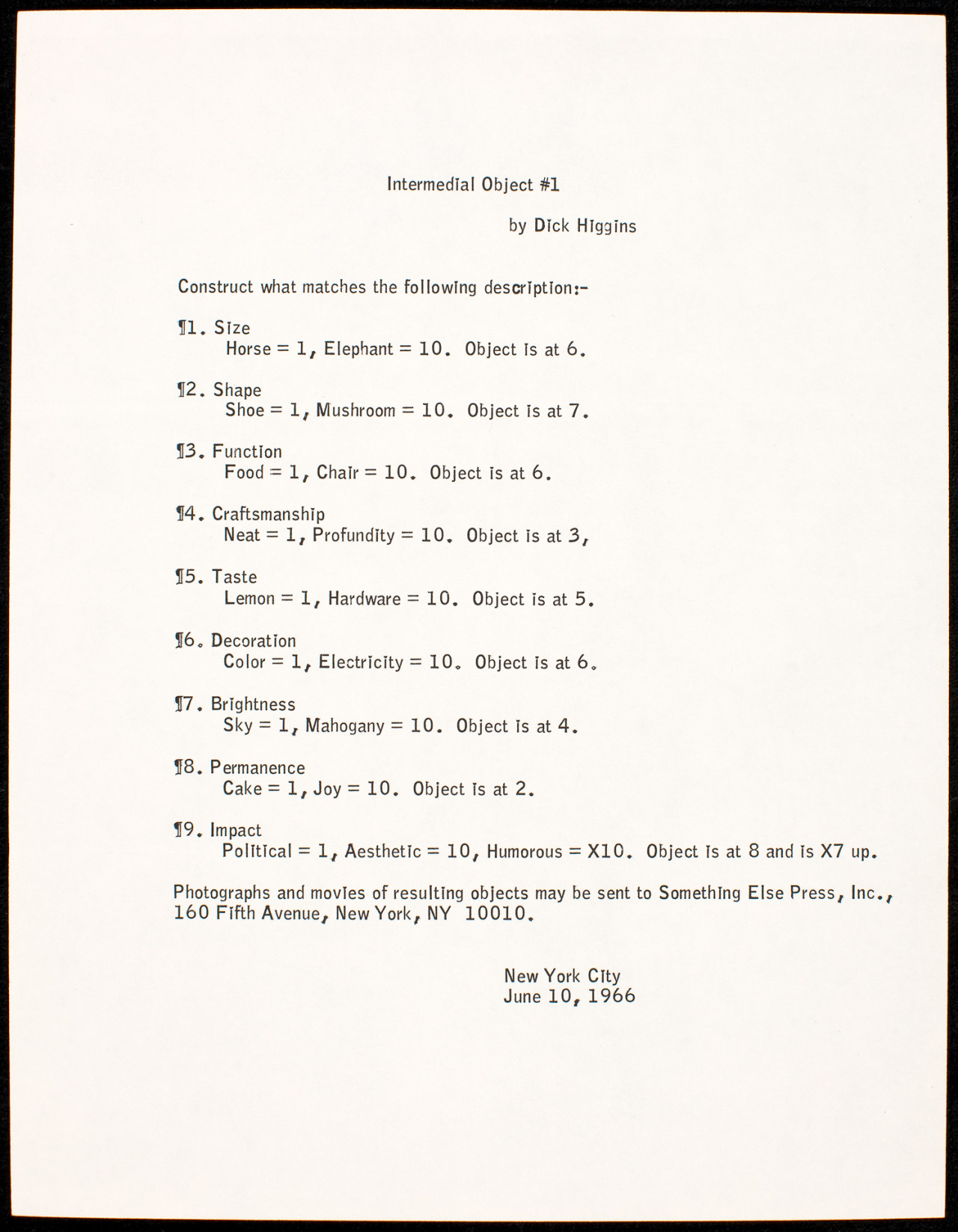

Fluxus artists’ innovative practices emerged from their engagement with multiple mediums at once—mediums that were set into new relations with one another, or coarticulated while remaining individually legible. The term “intermedia,” theorized by Dick Higgins, matched artists’ self-regard as de-professionalized, non-specialized agents who rejected the model of the modern artist as a specialist aligned with the figure of the midcentury bureaucrat. Instead, artistic occupations and their corresponding mediums were imagined by Higgins and his neo-avant-garde cohort as ever in transit, ever in relation, ever to be rethought in terms of one another. According to Higgins’s concept of intermedia, works are described as having the dimensions or qualities of multiple mediums at once, transforming the old modernist notion of medium from an increasingly restricted material ontology into a set of qualities or procedural operations. An intermedia work is not defined singularly as music, sculpture, or painting, but can be simultaneously musical, sculptural, and/or painterly. “In an intermedial work, such as a piece of action music,” Higgins explained, “the composition is a musical metaphor, where there may or may not be a musical notation” (Higgins, “Some Poetry Intermedia,” reprinted in A Dialectic of Centuries: Notes Towards a Theory of the New Arts, New York: Printed Editions, 1978, 17).

If the concept of intermedia reimagines individual mediums approaching one another through a kind of metaphorical relation, this rethinking of art’s forms and materials was an appropriate move for a group of artists who had always approached their various disciplines from an outsider position. Fluxus artists were composers and poets working like sculptors and painters, and so on. To imagine one medium as translatable into the language of another imagines a medium as a set of operations unattached to any particular set of materials, a notion that could only be arrived at via a notation-based practice like that of Fluxus. Through its concerts and publishing program, which internalized and advanced the musical lessons of the New York School, Fluxus developed an allographic as opposed to autographic model of iterative production, in which artworks—both performances and objects—were created or realized over and over again to differing results. For Earle Brown, the aesthetics of indeterminate or ambiguous works paralleled a generous notion, perhaps even an ethics, of subjectivity: “We recognize people regardless of what they are doing or saying or how they are dressed if their basic identity has been established as a constant but flexible function of being alive” (Earle Brown, quoted in Michael Nyman, Experimental Music: Cage and Beyond, London: Studio Vista, 1974, 58).

Fluxus artists’ search for alternative models of art’s production and distribution was fundamentally rooted in a creative reconceptualization of music. They defined music as a group of people being together, experimenting with a given set of rules, making sounds or not, but most importantly listening and paying very careful attention to one another and to the world. Fluxus artists applied this revised concept of music to the composition and circulation of scores, which embraced qualities of risk, failure, and experimentation while creating an opportunity for collective and collaborative production in varying times and places with always-differing performers and audiences. Importantly, despite all this risk, chance, and variability, a work’s rootedness in a score allows it to be continually understood as a particular work, and to maintain its identity in however loose a way despite the differences in its varied manifestations. A score can provide a very loose structure or form, but nevertheless, appreciable form remains.

Because of this flexibility and durability and strength, Fluxus scores still have something to give us, something to show us. They bring different things into relief in every environment and era in which they are performed. We might think, for example, of the work of Patterson and Knowles, which speaks to a subversive minor politics of race and gender, respectively. The subtle criticality of their work has led to its revival and recontextualization by contemporary artists interested in surfacing its implicit political connotations. As a result, we are increasingly able to appreciate how Fluxus practices explored and continue to explore a musical and philosophical notion of resonance, which appropriates the entire world as a sounding instrument.

Today, with the efflorescence in contemporary art and music of experimental forms of performance, sound, publishing, social practice, and new media, the impact of Fluxus seems to register everywhere. Many of these practices draw, knowingly or not, from the Fluxus milieu’s expanded understanding of a score—along with all that a score entails in terms of a work’s ontology, production, distribution, and reception. To help make sense of these resonances, we should recognize how Fluxus scores model and play with different modes of social regulation that organize the movement of bodies through space—from music, recipes, and games to architecture, ritual, and law. This last category was evidenced by the LA Phil’s first Fluxus Festival event, a realization of La Monte Young’s Composition 1960 #10 to Bob Morris by Archie Carey and David Allen Moore, which was halted prematurely by two LAPD officers.

Indeed, the best Fluxus and Fluxus-related work exposes how our lives are scored, orchestrated, or performatively designed for better or for worse, in both utopian and dystopian fashions. The most incisive revisitations of historic Fluxus pieces have recognized this. In Cut Piece for Pant Suits (December 2016), a public performance in Madison Square Park directed by JoAnne Akalaitis and Ashley Tata, ten women wearing pantsuits staged an homage to Yoko Ono’s 1964 Cut Piece at the very same time that members of the Electoral College were casting their votes for president. LA-based artist Elana Mann’s collaborative practice has generated edited anthologies of experimental scores written by contemporary artists, including works composed for a radical choir modeled after the People’s Mic, understood as a kind of political and aesthetic sonic instrument. Mann has also applied strategies from the practice of Pauline Oliveros to direct actions within the Occupy movement. More recently, she has transformed the “hands up, don’t shoot” gesture mobilized by Black Lives Matter into instruments for amplifying gestures of speaking and listening. Precisely because they understand the latent potential of Fluxus works to speak to the conditions of our present, many contemporary artists and collaboratives have been devotedly revisiting historical Fluxus and related pieces over the past years, including other LA-based entities such as the Southland Ensemble, Dog Star Orchestra, the wulf., wild UP, the LA Art Girls, and Machine Project.

These artists understand the contemporary use-value of the expanded field between art and music opened up by Fluxus. They utilize experimental notation and listening exercises to embrace experimentation, risk, and failure, knowing that they create opportunities for collective and collaborative action. Indeed, scores create temporary, intentional communities and intimate, roving commons in a moment when the simple fact of bodies gathering together in a public space can constitute a radical act.

Portions of this text have been adapted from Natilee Harren, “The Crux of Fluxus: Intermedia, Rear-Guard” and “The Inevitable Relationship Between Fluxus and Social Practice: Sarah Schultz Interviews Natilee Harren.”

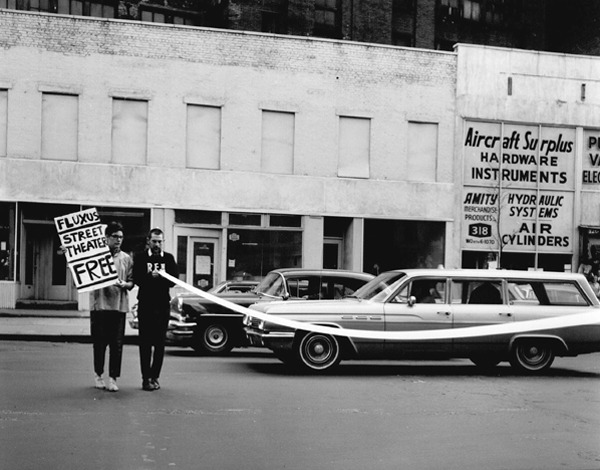

Images: Fig. 1, Alison Knowles and Ben Vautier perform Two Inches by Robert Watts, New York, 1964, photo by George Maciunas, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, Museum of Modern Art, New York; fig. 2, Nam June Paik, Alison Knowles, Emmett Williams, George Maciunas, and Benjamin Patterson performing Maciunas’s In Memoriam to Adriano Olivetti, Fluxus Internationale Festspiele Neuester Musik, Städtisches Museum, Wiesbaden, September 8, 1962, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, Museum of Modern Art, New York; fig. 3, George Brecht, Drip Music (Drip Event) (1959-1962), event score card and various realizations, 1962-c.1970; fig. 4, Willem de Ridder, European Mail-Order Warehouse/Fluxshop inventory with Dorothea Meijer, seated, in the home of the artist, Amsterdam, winter 1964–65, photo by Wim van der Linden/MAI, The Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection Gift, Museum of Modern Art, New York; fig. 5, Dick Higgins, Intermedia Object #1, 1966, Collection Walker Art Center, Minneapolis; fig. 6, Archie Carey and David Allen Moore perform La Monte Young’s Composition #10 1960 (to Bob Morris) with line chalkers and blue chalk in Los Angeles, September 30, 2018; fig. 7, Elana Mann, learning to live with the all of it, 2016 performance documentation at Commonwealth & Council, Los Angeles, photo by Devon Tsuno.

Natilee Harren is Assistant Professor of Art History at the University of Houston, where she teaches modern and contemporary art and theory. Her book, Fluxus Forms: Scores, Multiples, and the Eternal Network, is forthcoming from the University of Chicago Press in late 2019.

littleladofthecrypt liked this

littleladofthecrypt liked this minene-uryuu liked this

fluxuslaphil posted this