As ebony and rosewood become endangered, the likes of spruce, maple and boxwood are being scientifically modified to offer luthiers alternatives. Tom Stewart explores the brave new world of sustainable fittings

This article is from the 2019 Accessories supplement, available along with the June 2019 issue

Ebony trees take between 60 and 200 years to reach maturity. Even then, only one in ten trees felled has a black ‘core’ of sufficient size and quality for use in instrument making. ‘The rest are just left on the forest floor to rot,’ says Munish Chanana, co-CEO and head of research and development at Swiss Wood Solutions (SWS). A spin-off from Swiss university ETH Zurich and Empa, the Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials Science and Technology, SWS was founded in 2016 to develop natural alternatives to tropical hardwoods.

‘Only Madagascan ebony is protected by CITES (the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species) legislation at the moment,’ says Chanana. ‘But there’s little doubt the worldwide ebony trade will soon be restricted, as the sale of rosewood was in 2017.’ Given the extremely slow speed at which tropical hardwoods grow, it goes without saying that stocks have been depleted much faster than forests have been able to recover. ‘The problem is compounded by the vital role these trees play in the ecosystems where they occur, since they provide habitat and nutrients for a wide range of highly adapted species,’ Chanana adds.

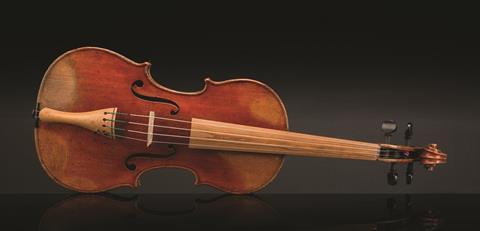

Luthiers have long relied on the density and hardness of woods like ebony and rosewood for making fingerboards, tailpieces, tuning pegs and other fittings, but now a number of so-called ‘technical’ woods – natural woods given physical or chemical treatments – have been developed to offer makers the same physical properties at reduced environmental cost. For musicians and dealers, CITES rosewood regulations require that any instruments containing rosewood must be registered and CITES-certified before they are bought or sold internationally. This administrative burden has led to increased interest in sustainable alternatives that match rosewood for look, feel and sound quality.

German luthier Daniel Hiller founded Berdani, a fittings maker, with his father Bernd in a bid to develop alternative materials using common and easily cultivated European woods. ‘We started making fittings about five years ago,’ he says, ‘and quickly became aware of the need to look beyond the traditional woods. In the end, we settled on two products: a rosewood substitute made from densified boxwood, and an alternative to ebony made from compressed paper.’

Through a combination of soaking the boxwood in water and heating it to high temperature, Hiller was able to increase its hardness to equal that of rosewood, often preferred for pegs on account of its durability and, of course, its colour – something else Hiller was able to achieve. ‘The process allows us to control the colour of the wood without the use of chemical dyes. It was very important for us to keep the wood free of acid, which can irritate the player’s skin as well as damage the varnish of the instrument.’

One of the first goals for SWS was to find an alternative fingerboard material to ebony. ‘Our research revealed three factors affecting fingerboard performance,’ explains Chanana. ‘To create a high-quality ebony substitute that sounded like the real thing, we had to achieve the correct density, hardness and dimensional stability. Repeated impacts from the player’s fingers require a hard surface resistant to denting and other deformations. Together, density and hardness are the variables that control the Q-factor – a measure of how well a substance is able to dampen sound waves as they pass through it.’

Working closely alongside SWS is Wilhelm Geigenbau, a Swiss firm of luthiers who also saw a need to experiment with alternatives to slow-growing tropical hardwoods. ‘The curator of the rainforest exhibit at Zurich zoo came to talk to us about the wider environmental impact of the ebony trade,’ says Wilhelm Geigenbau maker Boris Haug. ‘It made us realise the importance of making changes in our own work. We started by trying lots of local woods but even boxwood – which is the hardest of them all – was too soft. Next we looked into sustainable tropical hardwoods, but their Q-values were too high and the sound was shrill as a result. As Munish and his team have shown, however, it’s possible to densify local European woods in such a way as to lend them properties equal to those of ebony in this regard.’

According to Chanana, there is evidence that Roman and even ancient Egyptian society had some knowledge of how to increase the density of a piece of wood. Until recently, however, it has not been possible to create densified wood that was dimensionally stable. ‘All woods swell a little on contact with moisture,’ he explains, ‘but untreated densified wood can absorb a lot more water, and tends to spring back to its original size when it gets wet. We developed a way of using the chemistry of the wood cells themselves to lock in their size and, therefore, the density of the material overall.’ With fingerboards and instrument fittings in mind, SWS decided to work with maple and spruce, woods prized by luthiers for their sonority.

‘We densify maple by a power of two and spruce by a power of three to create Sonowood,’ he says. ‘Sonowood maple has approximately the same hardness and density as ebony, while the spruce product is slightly harder and more dense.’ Like that for the densified boxwood from Hiller’s Berdani workshop, the process employed by SWS relies mostly on water and heat.

‘We begin by impregnating the untreated wood with water and a catalyst to set off a reaction inside the cells that prevents them from returning to their original size and shape when they come into contact with water,’ Chanana explains. Although players can usually be relied on not to climb into the bath with their instruments, perspiration from fingers as well as moisture in the atmosphere is enough, says Chanana, to cause the densified wood to deform.

After the treated spruce or maple has been dried out somewhat, it is then subjected to what Chanana calls ‘hygrothermic densification’. ‘This is basically moisture plus heat plus pressure,’ he says. ‘There are numerous ways of doing it, but we compress the wood very, very slowly so as not to break the cell walls. Keeping these intact preserves the elasticity and internal structure of the wood, without which much of the sonic personality of the original would be lost.’ The tightly controlled conditions under which the densification process is carried out means that SWS is able to guarantee precisely the properties of Sonowood, and provide detailed specifications to help guide luthiers during the making process.

Another Swiss firm, Neo-Ebène, makes fingerboards from Corene, a composite material that includes resin and sustainable wood but no ebony. They contest the idea that only materials made from 100 per cent wood can achieve the same acoustic results as ebony. ‘The sound is the same,’ says engineer Pascal Henzi. ‘We’ve conducted laboratory tests that have shown the density and hardness to be the important factors.

The fact the material is not 100 per cent wood does not appear to make a difference.’ Pointing to the extra precision offered by such ‘technical’ materials in comparison with natural wood, Henzi’s colleague, luthier John-Eric Traelnes, also highlights their reliability. ‘Ebony is very different from one species to the next, and even between different trees of the same species,’ he says.

‘It was important for us to create something as uniform as possible. We wanted to offer our colleagues something they would be able to work in the same way as ebony, using the same tools, but without the problems associated with the gradual decline in the standard of available wood.’ Unlike Sonowood, Corene does not rely on the wood’s inherent chemistry to ensure its dimensional stability, but it does provide the same resistance to moisture and, with a hardness greater than that of ebony, wears out less quickly.

‘What colour is it? Is it black? Why isn’t it black?’ This is how Haug characterises the reactions of luthiers and fittings makers to the SWS product, which is brown, not black. ‘Violin makers can be very conservative,’ he says, ‘and a number of them rejected the material outright due to its colour.’ One need only think of the time and effort invested in antiquing new instruments to understand makers’ aversion to anything that looks too new, and Haug himself admits to having had concerns about the colour at first.

‘Black works with any varnish,’ he explains, ‘and doesn’t draw attention to itself. I was finally convinced, though, when we fitted a Stradivari with a fingerboard made from densified wood. It was a perfect match and, I think, enhanced the beauty of the instrument by allowing the shape of the f-holes to stand out more.’ Chanana points out another, more practical advantage: ‘The colour makes it clear to any customs official that it isn’t a tropical hardwood, saving time at the airport and potentially saving the instrument from harm.’

For those makers (and players) who prefer a black fingerboard, however, ebony is not the only option. ‘Our compressed paper product fills this niche,’ says Hiller. ‘Its physical characteristics have been modelled on those of ebony, and since it’s made from pulp rather than unprocessed wood, we are able to control the colour. In terms of feel and appearance, the difference from ebony is almost imperceptible.’ Corene is another all-black material, and Traelnes is clear on why this characteristic is important. ‘Rightly or wrongly, many people still expect to see a black fingerboard,’ he says. ‘We’re absolutely committed to eliminating ebony from instrument making altogether, but to do so requires an alternative that people don’t need much convincing to use.’

‘Some of the best sound adjustments we’ve made in our workshop have been using densified wood’ – Boris Haug

Although ebony is increasingly scarce, it does still remain the less expensive option – for now. Violin fingerboards made of ebony can cost as little as £20, whereas £70 is a typical price for one made from densified wood. But as Chanana points out, the situation is changing. ‘Ebony prices have doubled in the past twelve months,’ he says, ‘and that trend shows no sign of slowing down. At the same time, the growing popularity of densified wood is allowing us to expand our manufacturing capacity, driving down the costs passed on to the consumer.’ The same market forces apply to Berdani, too, where the differences in price are already smaller: four compressed-paper violin pegs for around £30 against £25 for ebony. In 2016 SWS received a grant of €1.5 million from the European Commission to support its research. ‘The grant gave us space to breathe,’ he says. ‘Without it we wouldn’t have been able to invest so much time creating a product that matches luthiers’ requirements so precisely.’

Neo-Ebène, whose Corene violin fingerboards cost around £50, is also expanding its range to include fingerboards and fittings for violas, cellos and basses. ‘Finding enough high-quality ebony for a ten-inch violin fingerboard is getting more and more difficult,’ says Henzi, ‘so you can imagine what it’s like when you start thinking about cellos or basses. We know that the future doesn’t lie with ebony, and we need to make those changes now.’

The moral imperative for makers to embrace alternatives to slow-growing tropical hardwoods seems clear. Although instrument making represents a tiny fraction of the trade in endangered tree species, new technologies are presenting luthiers with substitute materials that do not require compromise on look or sound. ‘In the same way that research makes you a better luthier, using new materials teaches you more about the instruments you’re building. Some of the best sound adjustments we’ve made here in the workshop have been using densified wood,’ says Haug.

Chanana makes his point more strongly: ‘People are used to cheap ebony,’ he says, ‘but unless they switch to a sustainable alternative they will have blood on their hands.’ Along with both Haug and Hiller, however, he is optimistic that, as makers become more familiar with ‘technical’ woods, they will feel more confident to use them in their own work. ‘We might all be happy and comfortable working with densified wood or compressed paper in my workshop,’ Haug says, ‘but each workshop is a world in miniature. It’s incumbent on us, now, to go out and show people just how good these materials are.’

Analysis April 2022: Seeing the wood for the trees

- 1

- 2

- 3

Currently reading

Currently readingOvercoming our addiction to tropical hardwoods: the latest alternatives

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- 9

- 10

No comments yet