The art of Chinese calligraphy has much to teach us about playing a stringed instrument, writes violist Hsin-Yun Huang

All art forms are mirrors of our inner selves. From writers to composers, from dancers to musicians, from artists to actors – the moment we are touched by inspiration, time stands still and we focus inward to create a transcendent artistic experience. It is every musician’s goal to communicate from the soul through music.

Ancient Chinese ideology taught that a cultured person was expected to study in six areas: etiquette, musicology, archery, chariot driving, literacy, and quantitative methodology and cosmology.

To explain each area further:

- Etiquette encompasses human and social behavior. It includes law, management and communication sciences

- Musicology includes music performance, popular culture, ceremonies, rituals and spirituality

- Archery broadly represents martial skills, sports and gentlemen’s competition

- Chariot driving stands for martial arts and physical culture

- Literacy includes reading, writing, literature, history and philosophy

- Quantitative methodology and cosmology stands for physics, arithmetic and mathematics.

Music comes second in this ranking and is seen in the same category as spirituality. How appropriate! For it is through spirituality that a musician finds his or her true voice.

String players use their bodies in an asymmetrical way. Good string playing is a combination of great left-hand action plus a musical right arm. It is interesting to think how our brains would need to work in order for the two parts to be liberated from each other. A tight left hand often means a tight right hand, which could translate to a stiff bow. A rigid right arm often means a lack of inner flow, which can surface in a stiff neck or inflexibility of the left arm. The key is cultivating a sense of flow from within.

As a child, I loved Chinese calligraphy. Each practice session would last two hours. During this time, there was often only silence. I would sit with my black inkstone, my rice paper and my study book, and practise stroke by stroke, character by character. It was one of my favourite activities, and I got good enough to represent my school for local competitions. This discipline involved cultivating a relaxed body and focused, clear mind, and a conscious way of coupling each stroke with the breath. The right hand built a relationship with the brush pen in much the same way as with a bow – gently guiding, yet at the same time allowing it to lead. Calligraphy became an opportunity for meditation in my busy middle school schedule.

In Chinese calligraphy, every little factor affects the overall result. For example, when you wet the inkstone and grind it, the amount of water versus how many turns you give the ink stick affects the intensity of the darkness. Like other art forms, once the brush pen touches the paper there is no going back. There is only one direction and one try. If you linger too long – by even half a second! – the ink soaks through the rice paper and the shape of the stroke is ruined.

The process of writing Chinese calligraphy requires us to think through the strokes before the pen touches the paper. One might say there is a right ‘tempo’ and ‘rhythm’ to a specific stroke: when to go fast and slow, when to pause just the right amount, when to finish with a flourish. There is immense patience involved in watching great masters at work: the act is timeless, and they often appear to know exactly how it will end.

Calligraphy and string playing share much in common. They both require us to activate the ’mind’s eye’ and ’mind’s contemplation’. Through strengthening our mind’s eye, we practice the imagined stroke in our head before action. Through mind’s contemplation, we reveal the spiritual and transcendental aspects of both calligraphy and music. A beginner calligrapher practices ’oneness’ over and over before moving onto more complex strokes. Oneness is represented in a dot and one horizontal stroke – which literally means the number one (Yi) in Chinese. It is much like string playing when we need to start by feeling the strings for articulation, then move onto practising open strings over and over again – cultivating flow – before we can even add the left hand.

The Western modern bow evolved from the Byzantine Empire of the mid-5th century. These primitive bows were convex like an archery bow. During the Baroque era, playing techniques developed further and the structure of the bow needed to change in order to improve control. Instead of calling the directions of the bow ‘up’ and ‘down’ in today’s terms, the French use pousser (push) to indicate upbow and tirer (pull) to indicate downbow. When we imagine push and pull, all of a sudden the feeling of weight in the sound becomes present. Just like with a brush stroke, it is in the act of pulling and pushing the hair in such an attentive way that the calligrapher attains mastery over his or her writing.

There is a Chinese saying 字如其人; it means ‘you can read a person by his calligraphy’. If the mind and the brush are united, then the calligraphy has soul and communicates the artist’s heart. Is it not the same with sound? We know that we can instantly identify the sound of great players. The indescribable quality of hearing an honest voice – it can be expressive, loving, joyous, humorous, grieving, or grateful, but most of all, it is the vulnerability in the sound that touches us. There is no hiding on stage; we are there to write our own musical calligraphy.

-

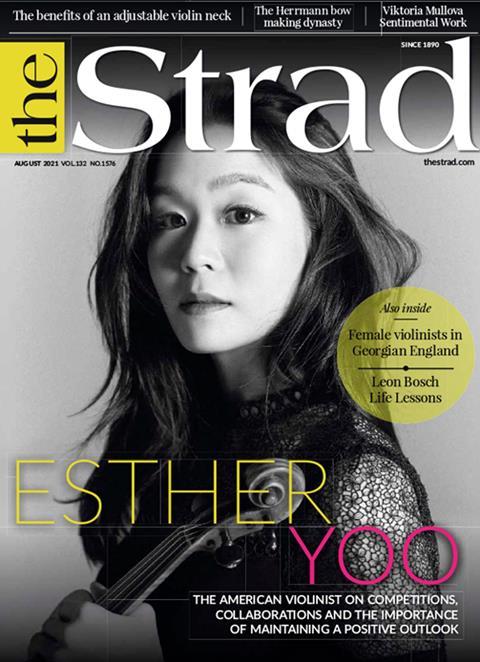

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet