How Beethoven’s iconic ‘da-da-da-dum’ motif was almost lost in a forgotten piano piece

13 January 2022, 17:23 | Updated: 17 January 2022, 13:40

The UK’s leading scholar on Beethoven has found that the famous opening of the Fifth Symphony began life with a totally different purpose...

Listen to this article

Classical connoisseur, and music novice alike will recognise the famous four-note opening motif of Ludwig van Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony.

The ominous introductory theme appears in modern media, such as movies, and was also used during the Second World War as a symbol for Victory. The famed ‘da-da-da-dumm’ motif mirrored the rhythm used for the letter V in Morse code (short-short-short-long).

However, the origins of the opening theme have remained relatively unexplored, or understood; until now.

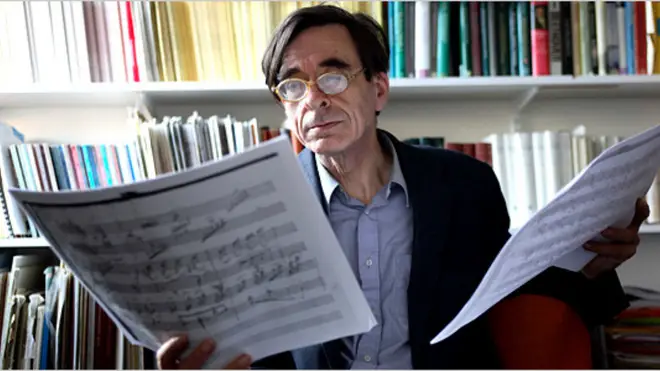

Thanks to the investigations of Professor Barry Cooper, the UK’s leading scholar on the German composer, it’s been revealed that classical music’s most iconic motif was almost simply a subsidiary theme meant for a forgotten piano piece.

Read more: Unheard Mozart piano piece performed to mark composer’s 265th birthday

Beethoven: Symphony No. 5, First movement (Benjamin Zander, Boston Philharmonic Orchestra)

In 1804, four years before the Fifth Symphony’s first performance, Beethoven wrote out the sketches of the opening theme of his next symphony.

Scholars have used this manuscript as a source of sketches for the Fifth Symphony however, thanks to Cooper’s further investigation into the score, it is clear that Beethoven was not in fact sketching a symphony – but a piano fantasia.

“It became abundantly clear to me that [these sketches were] part of the projected piano fantasia, which was being sketched immediately above the sketch in question,” explained Cooper. “I studied the page in detail as I am writing a book on ‘The Creation of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies’.”

Cooper, who is a professor at the University of Manchester, is best known for his books on Beethoven, as well as a completion and realisation of Beethoven’s fragmentary Symphony No. 10.

Read more: Beethoven’s unfinished Tenth Symphony completed by artificial intelligence

“The fantasia (so-called in the sketch) is in C minor, like the [fifth] symphony. Like most fantasias of the period, it would be based on contrasting sections and ideas, so the opening section is in a slow 3/8, contrasting with the later 2/4 that uses the motif that ended up in the symphony.

“The motif is then developed in the 2/4 section in a symphonic manner – which may be why Beethoven concluded it would work better in a symphony – but using piano textures rather than orchestral ones, and in a different way from how it is developed in the symphony.”

Professor Cooper notes that the find gives us a deeper understanding of how Beethoven worked as a composer.

“The sketch shows that he was prepared to transfer ideas intended for one composition into a completely different one, if it would work better there.”

Cooper surmises that Beethoven felt exactly that way about this motif, and adds the composer “strengthened the motif by placing it at the head of a symphony, and then strengthened it still further by adding dramatic pauses in later sketches and the final version”.

Read more: German pop singer calls for Beethoven’s body to be exhumed for a racial DNA test

Amazing performance sees Beethoven's 5th performance with percussion by students in France

Classic FM presenter, and our very own authority on Beethoven, John Suchet, said in light of Professor Cooper’s discovery, “This is very exciting news for anyone interested in Beethoven’s creative process.

“We know, from the many sketchbooks that have survived, that Beethoven would work on several compositions at once, with fragments appearing on the same page that he would later use in different compositions.”

Suchet adds, “It is no surprise that the famous opening of the Fifth Symphony may have begun life with a totally different purpose. That was how Beethoven worked. Discoveries like this add enormously to our understanding of him.”