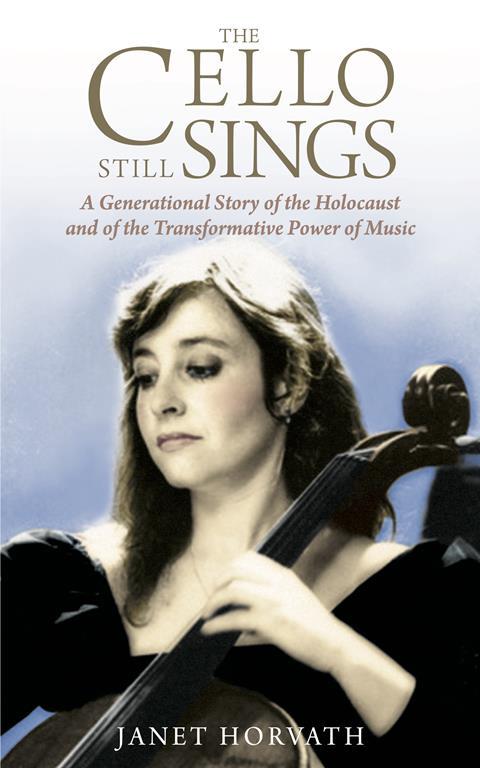

To mark International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January, author and cellist Janet Horvath presents an excerpt from her forthcoming memoir The Cello Still Sings: A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

International Holocaust Remembrance Day on 27 January marks the day when Auschwitz-Birkenau, the largest and most heinous Nazi death camp of World War II, was liberated. Millions perished, and many more millions were irrevocably scarred — survivors, liberators, and the subsequent generation of children of survivors. I am one of them.

Although my parents evaded being shipped to a death camp, my father was rounded up for slave labour at the copper mines of Bor, Yugoslavia, and my mother, only seventeen at the time, hid in coal bins and under lumber and rubble, while Budapest was under siege and bombarded late in the war.

My parents, who survived and were able to start life anew in Canada, never spoke about their experiences.

As a child I was haunted by the eerie hush surrounding my parents’ experiences. George and Katherine, two professional musicians, buried the memories of who and what they were before, silencing the past in order to live. Music was their lifeline.

After five decades of secrets, I stumbled upon a clue. I asked my father an innocent question about music. He revealed that after the war, he performed 200 morale-boosting concert programmes throughout Bavaria from 1946–48 in a 20-member orchestra of concentration camp survivors. Although I also become a professional cellist, my father had never disclosed that two of the programmes, in 1948, were led by the legendary American maestro Leonard Bernstein. It was the catalyst that led to my father telling me his story.

In 2018, the town of Landsberg, Germany, planned a commemorative programme upon the 70th anniversary of the 1948 performances with Bernstein. I was invited to play the cello solo Kol nidrei by composer Max Bruch with an orchestra of German youth. My family and several others whose parents had languished in the DP camp in Landsberg joined the townspeople in Landsberg for what turned out to be an out-of-body and reconciliatory experience – the lingering scars healed through the sustenance and power of music.

Here is an excerpt from my new book The Cello Still Sings: A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music, to be published on 28 February by Amsterdam Publishers.

A CONCERT WITH LEONARD BERNSTEIN IN MAY 1948

He’d already called three times that morning. ”Janetkém. When you are coming?” With a firm grip on the steering wheel, I slalomed the car forward on black, ice-covered roads toward my father’s high-rise. The dense traffic and the treacherous surfaces hindered my progress. I chose a circuitous route, unplowed but easier to negotiate. With shoulders raised to my ears, I slid into a parking spot and braced myself for the cold trek to the front door. My elevated pulse didn’t surprise me. The dusky sky threatened more sleet, and I was nearly late.

The elevator door opened onto the 14th floor, and there stood my father, clean-shaven, waiting in his camel hair coat and jaunty black chapeau. Underneath, as always for any outing, he was dressed in a suit—the gray pinstriped one with a crisp tailored shirt, multicolored matching silk tie, leather shoes tied just so.

Raising his unruly eyebrows, now speckled with gray, he said with a twinkle in his eyes, “Janetkém, where were you so long?”

We embraced and made our way painstakingly into the elevator.

My father at 87 was still sharp, critical, astute; his old-world European elegance and high standards of behavior were unchanged; his taste in fashion, art, and cuisine uncompromised; and his thick Hungarian accent undiminished. Still, the least slight could set him aflame. He leaned precariously on his walker. When had his posture become so stooped, his physique so frail? He would often forget about his unsteadiness, which had resulted in sudden falls.

As we left the building buffeted in the subzero wind tunnel, I was grateful I hadn’t chosen this location for my parents, because I would never have heard the end of it. My father loved all things beautiful. He selected this building because of the striking gold fixtures in the bathroom and contemporary marble tiled floors. The lobby of the multistory condominium located on Yonge Street, the main north- south corridor of Toronto, exudes refinement with its leather furniture, floor to ceiling mirrors, and luxuriant plants—a monolith above the bustling street. But the steep incline between the parking lot and the entryway is difficult even for young people to negotiate. The first week my parents lived there, my father fell flat on his face, breaking his nose. A superstitious man, he decided the place was cursed.

Leaning into the wind, I tightened my hold on him. We lumbered to the car, then I reminded him to place his behind in first and to lower his head so he wouldn’t bump it on the way in. I bent down to grab his legs and hoisted them into the car. Success. No bruises or breaks this time. Once I had heaved the walker into the trunk, I settled into the driver’s side, sighing audibly in anticipation of the tedious drive to yet another doctor’s appointment, this time the neurologist, for his Parkinson’s disease symptoms.

”Watch how you are driving, Janetkém.”

Still uneasy, I focused on the rugged inflection of his voice, the sound of his fingers tapping on the center console. Cello-playing fingers need to be supple. He was always practicing even without the instrument, even on an armrest, even now that he no longer played. This life-long mannerism temporarily impeded the oscillating tremor in his limbs.

Book review: Violins and Hope: From the Holocaust to Symphony Hall

Read: Israeli Holocaust violin restorer receives award for service

Read: Remembering the Holocaust: Noah Max on ’A Child In Striped Pyjamas’

I considered harmless subjects for conversation and settled on music. He loved to talk shop. My orchestra was preparing a festival to honor Leonard Bernstein—the legendary maestro, educator, and pianist, bad boy and superstar—the genius who composed West Side Story; who for nearly half a century conducted the New York Philharmonic.

Despite more than three decades of cello playing, I never crossed paths with Bernstein. But my father, a wonderful cellist in his day, performed under the batons of the greatest conductors as a member of first the Budapest Symphony and then the Toronto Symphony.

He was quite hard of hearing by then, so I hollered, “Papa. Did you ever play with Leonard Bernstein?”

The tapping stopped. His skin paled. He shifted in his seat, rubbed his rheumy eyes, and placed the palm of his hand on his cheek. Several moments passed. Should I pull over? I decided to remain quiet, concentrating on the road, when a whoosh of air escaped from his lungs.

“Yes,” he said. “It was very hot day. He came. To conduct Jewish Orchestra in DP camps. In 1948. After war. He played George Gershwin Rhapsody in Blue on piano. He was just a kid and was just fan-tas-tic! ‘Gentlemen,’ he said, ‘let’s take off our jackets and roll up our sleeves. We are just schvitzing!’” My father laughed. “I talked to him… in German. I said, ‘I want come to America.’ So warm Bernstein was. He said I am great Jewish musician. I should go to Palestine.”

Perspiration oozed down my neck. Resisting the urge to brake, I considered what to do. He’d never told me this story before, or others. Ice pellets strafed the car and my father, a defiantly taciturn man, had just disclosed a long-held secret. Hoping for more, hoping not to intrude, I kept driving.

He always remembered the music—a Weber overture preceded Rhapsody in Blue, and a beautiful young girl named Henia thrilled the audience with Yiddish and Hebrew songs.

“Chaim Arbeitman, fan-tas-tic violinist, played solo. What a tone! Younger than me—maybe 18 he was? He changed his name when he came to America—to Arben? David Arben? He was accepted by Philadelphia Orchestra,” my father said proudly, as if it was his own accomplishment. “We played for 5,000 people. Everybody needed music, needed to hear Bernstein.”

My father’s face glowed as he evoked Bernstein, his luxuriant hair tumbling down his brow, his vivid personality, his exuberant gestures. And during the passion-infused piano-playing of Rhapsody in Blue, his body swaying for emphasis, he led the ensemble with a mere nod of his head, a swivel of his hips, a shrug of his shoulders. My father recalled the healing power of the music, not the hardship and the deprivation of the times.

Like other Holocaust survivors, Papa rarely, if ever, alluded to his experiences during or after the war. What had my question unleashed?

Thoughts sprinted through my mind. How and when did he go to Germany, of all places? Was my mother there, too? Were they displaced persons? Why had he never before boasted about the encounter with Bernstein?

“But Papa. How did you—?”

My father shrank in his seat and huddled closer to the passenger door. He shook his head; his eyes turned grave. Tapping, and staring straight ahead, he reverted to silence.

The Cello Still Sings: A Generational Story of the Holocaust and of the Transformative Power of Music will be published on 28 February by Amsterdam Publishers.

https://www.amazon.com/author/janet.horvath.cellist

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet